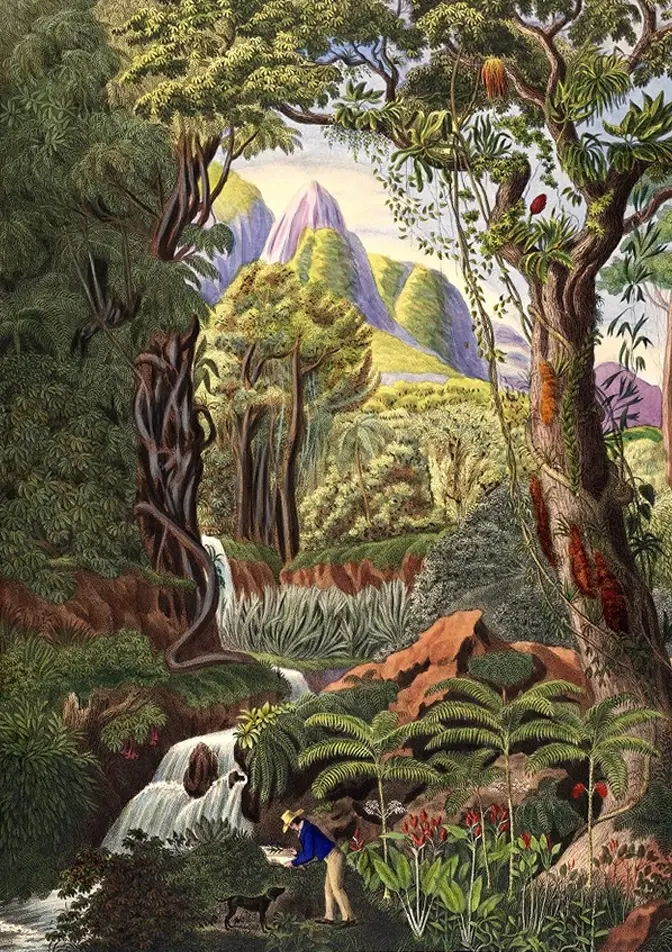

Eine Botanisierbüchse wurde verwendet, um Pflanzen, Samen und Insekten zu sammeln. Man konnte sie damit sicher transportieren, ohne sie zu beschädigen. Das half Botanikerinnen und Botanikern, Pflanzen im Detail zu studieren. Zum Beispiel die Anordnung der Blütenblätter, die sonst während des Transports beschädigt werden konnten.

Das Pressen von Blumen in einer Pflanzenpresse oder einem Buch war eine beliebte Methode, um Pflanzen haltbar zu machen. Das war aber bei schlechtem Wetter oder in gefährlichen Situationen nicht immer einfach. Viele Sammler benutzten deshalb Botanisierbüchsen und tragbare Pressen. Manche steckten sich die Insekten für den Transport sogar an ihren Hut!

Die meisten jungen Leute halten die Botanik für ein langweiliges Studium. Das ist sie auch, so wie sie in den Lehrbüchern der Schulen gelehrt wird; aber studiere sie selbst auf den Feldern und in den Wäldern, und du wirst feststellen, dass sie eine Quelle immerwährender Freude ist.

John Burroughs (1837-1921), amerikanischer Naturforscher und Naturschützer

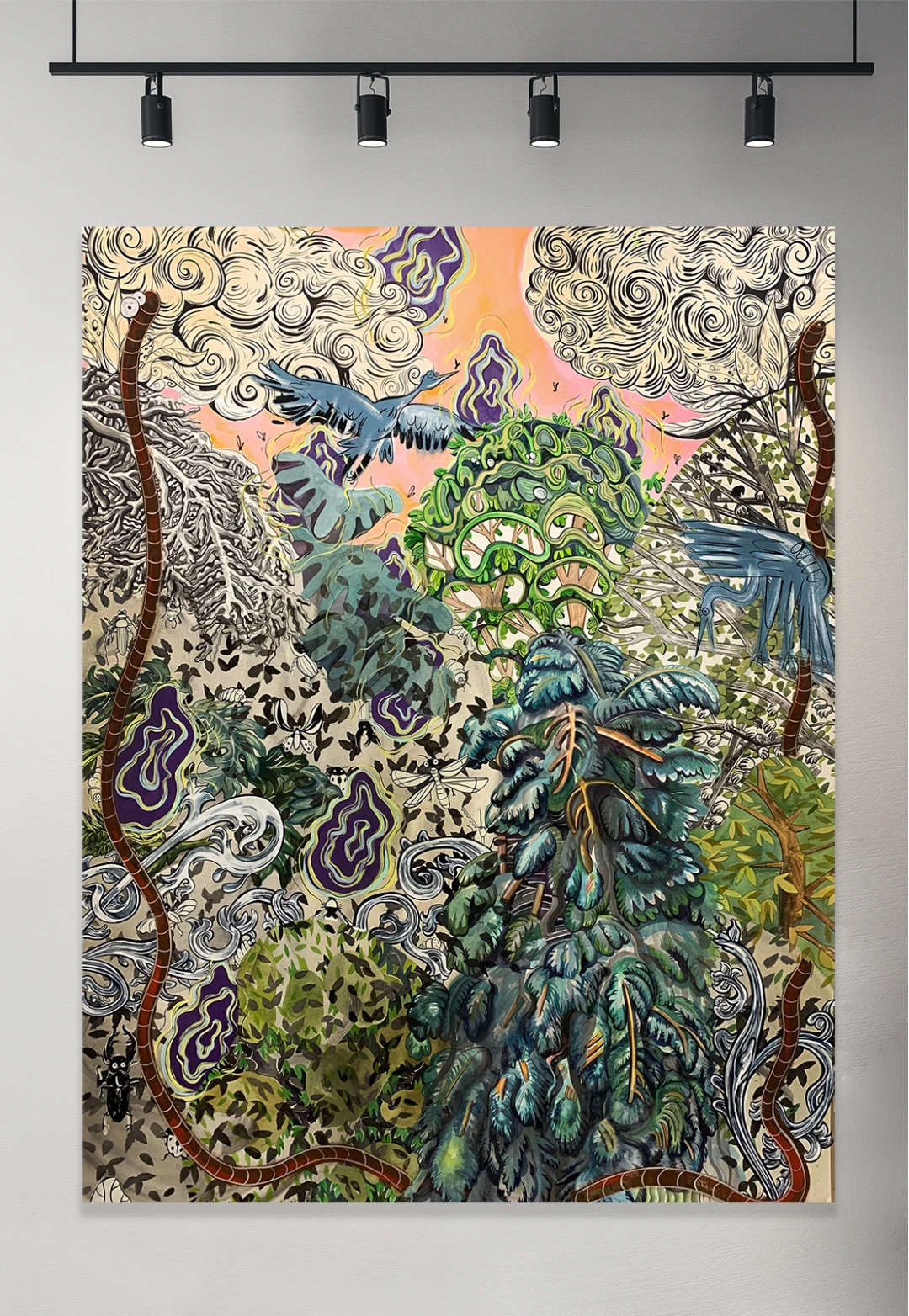

Pflanzenjäger/innen und ihre Botanisierbüchsen

Pflanzensammlungen

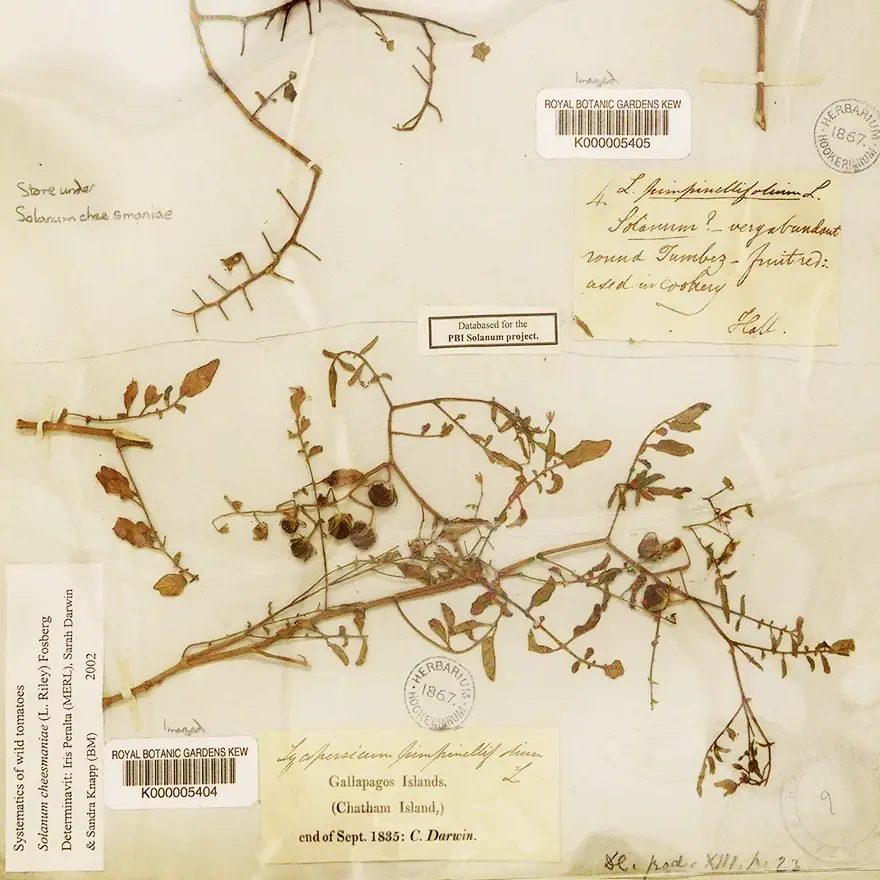

Zwischen 1700 und 1900 nutzten Botanikerinnen und Botaniker die Botanisierbüchse, um die auf ihren Reisen gesammelten Pflanzen nach Hause zu bringen. Sie legten ihre eigenen Pflanzensammlungen (Herbarium) für weitere Studien an.

Der Aufbau einer Pflanzensammlungen erfordert ein systematisches und schrittweises Vorgehen: Sammeln der Pflanzen, Identifizierung, Pressen mit Pflanzenpressen, Trocknen, Aufziehen auf Platten mit Etiketten, Konservierung und Lagerung.

Botanische Gärten und ihre Forschungseinrichtungen auf der ganzen Welt bewahren mehr als 3’000 gepresste Pflanzensammlungen auf, von denen viele Jahrhunderte alt sind.

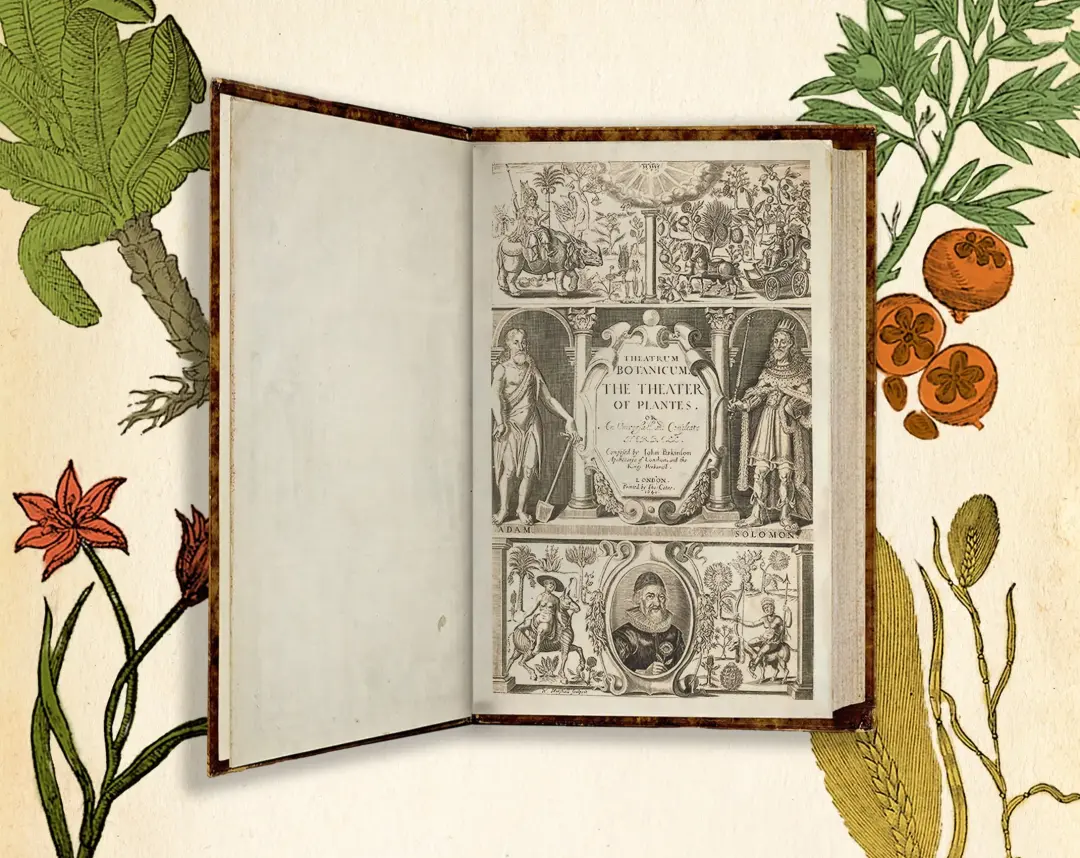

Das älteste noch existierende Herbarium wurde vom italienischen Naturforscher Gherado Cibo im 16. Jahrhundert angelegt.

Die grössten Sammlungen getrockneter Pflanzen befinden sich in folgenden Institutionen: Naturhistorisches Museum in Paris; Royal Botanica Gardens in Kew: über 7 Millionen Exemplare, die bis ins Jahr 1696 zurückreichen; William and Lynda Steere Herbarium im New Yorker Botanical Garden: 7,8 Millionen Exemplare, die zweitgrößte Sammlung der Welt.

Herbariensammlungen sind neben Samenbanken und Pilzsammlungen von entscheidender Bedeutung für die Erforschung und Erhaltung der Artenvielfalt.

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) legte eine der ersten Pflanzensammlungen im "Jardin des plantes" in Paris für König Ludwig XIII. an.

Die Universität Neuchâtel in der Schweiz besitzt über 475’000 Tafeln mit Pflanzen, die für Wissenschaft und Studium digitalisiert werden. In der Vergangenheit haben Philosophen und Schriftsteller wie Jean-Jacques Rousseau immer wieder betont, wie wichtig das Wissen über die Natur ist. Er lebte im Zeitalter der Aufklärung, in dem wissenschaftliche Beweise an Bedeutung gewannen.

Es ist wichtig zu wissen, woher Museumssammlungen stammen und wie die Objekte dorthin gekommen sind. Besonders für botanische Gärten wie Kew Gardens, die eine koloniale Geschichte haben. Sie nutzen heute Technologie, Forschung und Vermittlungsprogramme, um den Zugang zu ihren Sammlungen und das Verständnis für sie zu verbessern.

Botanische Gärten in aller Welt

80% der Biodiversität

Indigene Völker besitzen wichtiges Wissen über lokale Pflanzen und deren Verwendung. Botaniker verliessen sich oft auf ihr Wissen, wenn sie neue Gebiete erkundeten. Heute werden 80 % der biologischen Vielfalt der Welt von indigenen Gemeinschaften geschützt. Ein Viertel der weltweiten Landfläche gehört indigenen Völkern, wird von ihnen verwaltet, genutzt oder bewohnt.

Sammeln oder bewahren?

Die amerikanischen Ureinwohner Nordamerikas lernten ihr Wissen über Pflanzen und Tiere von ihren Ältesten. Diese haben ihre Ideen und ihr Wissen oft über Generationen hinweg weitergaben. Ein Grossteil dieses Wissens wurde erworben, ohne dass die Natur gesammelt oder gefährdet wurde, um sie zu studieren. Heutzutage sind viele Pflanzen vor dem Sammeln geschützt, weil sie gefährdet sind.

Was ist Fortschritt?

Indigene Völker haben eine einzigartige Art, die Natur zu verstehen und mit ihr in Beziehung zu treten. In der Vergangenheit wurde dies als das Gegenteil des Fortschritts angesehen. Man fand Dinge wie Eisenbahnen, Fabriken und Technologie wichtiger. Heute achten viele Menschen auf das Wissen und die Lebensweise indigener Völker. Sie können helfen, die Umweltverschmutzung zu verringern und die Natur zu schützen.

Möchtest Du mehr erfahren?

Bibliografie

GESCHICHTE DER BOTANIK

Hodacs, H. (2018). Linnaeus, natural history and the circulation of knowledge. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

Le Guyader, H., & Norwood, J. (2018). L’aventure de la biodiversité : de Ulysse à Darwin, 3000 ans d’expéditions naturalistes. Paris: Belin.

PFLANZENJÄGER

Barrow, Mark V. (2000). “The Specimen Dealer: Entrepreneurial Natural History in America’s Gilded Age,” Journal of the History of Biology 33 (2000).

Carine, M. (2020). The collectors: creating Hans Sloane’s extraordinary herbarium. Natural History Museum.

Lemmon, K. (1968). The golden age of plant hunters. [éditeur non identifié].

Chacko, Xan Sarah (2018): When life gives you lemons: Frank Meyer, authority, and credit in early twentieth-century plant hunting. History of Science 2018, Vol. 56(4) 432 –469 DOI: 10.1177/0073275318784124 journals.sagepub.com/home/hos

Cunningham, Isabel Shipley, Frank N. Meyer (1984): Plant Hunter in Asia. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

De Vries, Hugo, The Mutation Theory: Experiments and Observations on the Origin of Species in the Vegetable Kingdom, Vol. 2 (Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company, 1909)

Edwards, A. (2021). The plant-hunter’s atlas: a world tour of botanical adventures, chance discoveries and strange specimens. Greenfinch, an imprint of Quercus Editions Ltd.

Endersby, J. (2008), Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008)

Fry, C. (2009). The plant hunters: The adventures of the world’s greatest botanical explorers. Andre Deutsch.

Garland E. Allen (1969) “Hugo de Vries and the Reception of the Mutation Theory,” Journal of the History of Biology 2 (1969): 55–87

Harris, A. (2015). Fruits of Eden: David Fairchild and America’s plant hunters. University Press of Florida.

Kingsbury, Noël, Hybrid (2009): The History and Science of Plant Breeding (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009)

BOTANIKERINNEN UND PFLANZENSAMMLERINNEN

Bilston, S. (2008). Queens of the garden. Victorian women gardeners and the rise of gardening advice text. . Victorian Literature and Culture, 36(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150308080017

The Dietrich Project – Virtual exhibition about the work and findings of the German, self-taught botanist and plant hunter Amelie Dietrich. Figueiredo, E., & Smith, G. F. (2021). Women in the first three centuries of formal botany in southern Africa. Blumea, 66(3), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2021.66.03.10

Logan, G. B. (2004). Women and botany in risorgimento Italy . Nuncius, 19(2), 601–628. https://doi.org/10.1163/182539104X00377

Madsen-Brooks, L. (2009). Challenging science as usual. Women’s Participation in American Natural History Museum Work, 1870-1950. Journal of Women’s History, 21(2), 11–38. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.0.0076

Olsen, P. (2013). Collecting ladies : Ferdinand von Mueller and women botanical artists. Canberra, ACT: NLA Pub.

Rindlisbacher, J., & Cohen, A. (2020). Growing Wild: The Correspondence of a Pioneering Woman Naturalist from the Cape. Oxford: Basler Afrika Bibliographien. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1b0fx9w

Shteir, A. B. (1996). Cultivating women, cultivating science : [Flora’s daughters and botany in England 1760 to 1860]. Baltimore [et autres: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tepe, E. J., Ridley, G., & Bohs, L. (2012). A new species of Solanum named for Jeanne Baret, an overlooked contributor to the history of botany. PhytoKeys, 8(8), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.8.2101

DER WARDIAN CASE

Keogh, L. (2017). The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved the Plant Kingdom. Arnoldia, 74(4).

Liu, H.-Y. (2012). From cabinets of curiosities to exhibitions: victorian curiosity, curiousness, and curious things in charlotte brontë. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Shirai, Y. (2003). Ferndean: Charlotte Brontë in the Age of Pteridomania. Brontë Studies : Journal of the Brontë Society, 28(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1179/bst.2003.28.2.123

BOTANIK DER KOLONIALZEIT

Allain, Y.-M. (2013). Une Histoire des Jardins Botaniques: Entre Science et Art Paysager. Versailles: Quae.

Ayers, E. (2019). Strange Beauty: Botanical Collecting, Preservation, and Display in the Nineteenth Century Tropics. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Endersby, J. (2016). Deceived by orchids: sex, science, fiction and Darwin. The British Journal for the History of Science, 49(2), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087416000352

Grove, Richard(1995), Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Hong, J. (2021). Angel in the House, Angel in the Scientific Empire: Women and Colonial Botany During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, 75(3), 415-438. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2020.0046

Kingsland, Sharon E.(2005), The Evolution of American Ecology, 1890–2000 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005)

Klemm, D. (2020). Foraged flora : exploring the culinary potential of wild edible plants. University of Georgia Press.

Kloppenburg, Jack Ralph (1988), First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 1492–2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988)

Rice, R. (2020). “My dear Hooker”: the botanical landscape in colonial New Zealand. Museum History Journal, 13(1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/19369816.2020.1766296

Royal Botanic Gardens, K. (n.d.). Indian and Colonial Botanic Gardens - The Pamphlet Collection of Sir Robert Stout: Volume 6. Victoria University of Wellington Library, Wellington.

Swan, Claudia (eds.), Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 200

PFLANZENJÄGER

Bush, E. (2012). The Plant Hunters: True Stories of Their Daring Adventures to the Far Corners of the Earth (review). Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books, 65(9), 480–480. https://doi.org/10.1353/bcc.2012.0407

Butler, S. A. (2016). A Plant Hunter’s Legacy: Japanese Trees in a New England Landscape, 1870–1930. Winterthur Portfolio, 50(2/3), 99–149. https://doi.org/10.1086/688739

Chacko, X. S. (2018). When life gives you lemons: Frank Meyer, authority, and credit in early twentieth-century plant hunting. History of Science, 56(4), 432–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0073275318784124

Edwards, A. (2021). The plant Hunter’s atlas : a world tour of botanical adventures, chance discoveries and strange specimens. London: Greenfinch.

Musgrave, T., Gardner, C., & Musgrave, W. (2000). The plant hunters: two hundred years of adventure and discovery around the world. London: Seven Dials. Primrose, S. B. (2019). Modern Plant Hunters: Adventures in Pursuit of Extraordinary Plants. London: Pimpernel Press.

Short, P. (2003). In pursuit of plants : experiences of nineteenth & [and] early twentieth century plant collectors. Portland: Timber Press.

PFLANZEN- UND SAATGUTWIRTSCHAFT

Mabey, R. (2015). The cabaret of plants: botany and imagination. Profile Books Ltd.

Saunders, G. (1995). Picturing plants: an analytical history of botanical illustrations. University of California Press.

Secord, Anne (1994), “Science in the Pub: Artisan Botanists in Early Nineteenth-century Lancashire,” History of Science 32 (1994): 269–315

INDIGENES WISSEN ÜBER PFLANZEN UND DEREN SCHUTZ

Clarke, P. A. (2008). Aboriginal Plant Collectors. Botanists and Australian Aboriginal People in the Nineteenth Century. Rosenberg Publishing. ISBN: 9781877058684.

Shiva, V. (1992). Women's Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation. India International Centre Quarterly, 19(1/2), 205-214.

EMILY DICKINSON, GARDENING AND POETRY Bianchi, M. D. (1990). Emily Dickinson’s Garden. Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin, 2(2), 1-2, 4. Farr, J. (2004). The Gardens of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press. McDowell, M. (2019). Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life. Timber Press. Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium. (n.d.). Harvard’s Houghton Library. Retrieved from http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/4184689?n=1&res=3&imagesize=1200