Vasculum, presses and hats!

A vasculum, or botanical box, was used to collect and safely transport plants, seeds, and insects without damaging them. It helped botanists study plant details – such as petal arrangement - that might otherwise shift during transport.

Pressing flowers in a plant press or book was a popular method. But doing so in extreme weather or dangerous conditions wasn’t always easy. Many collectors used both vasculums and portable presses, and even pinned insects to their hats for transport!

Most young people find botany a dull study. So it is, as taught from the textbooks in the schools; but study it yourself in the fields and woods, and you will find it a source of perennial delight.

John Burroughs (1837-1921), American naturalist and nature conservationist

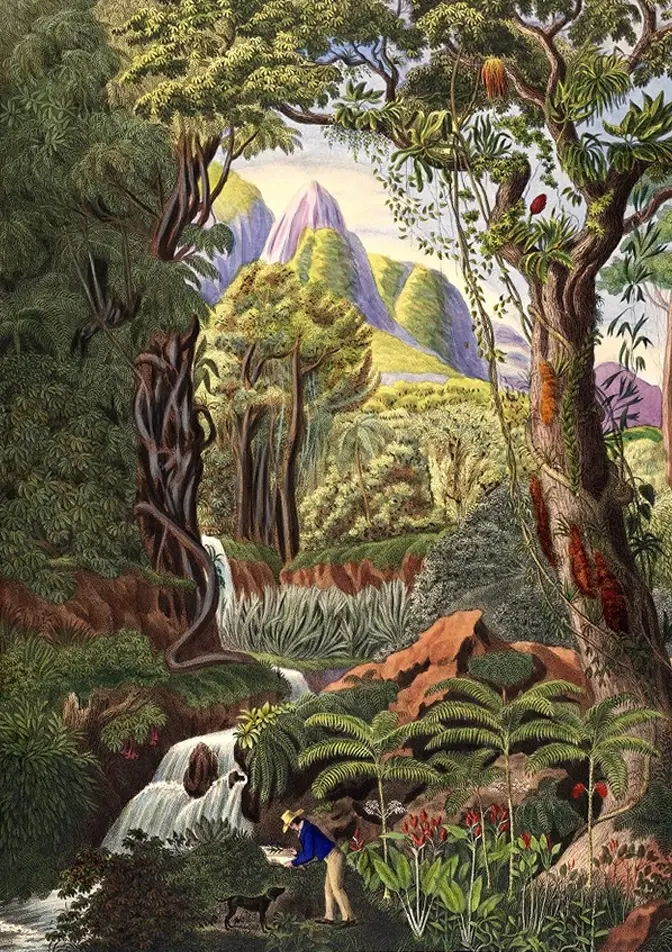

Plant hunters and their botanical boxes

Plant collections

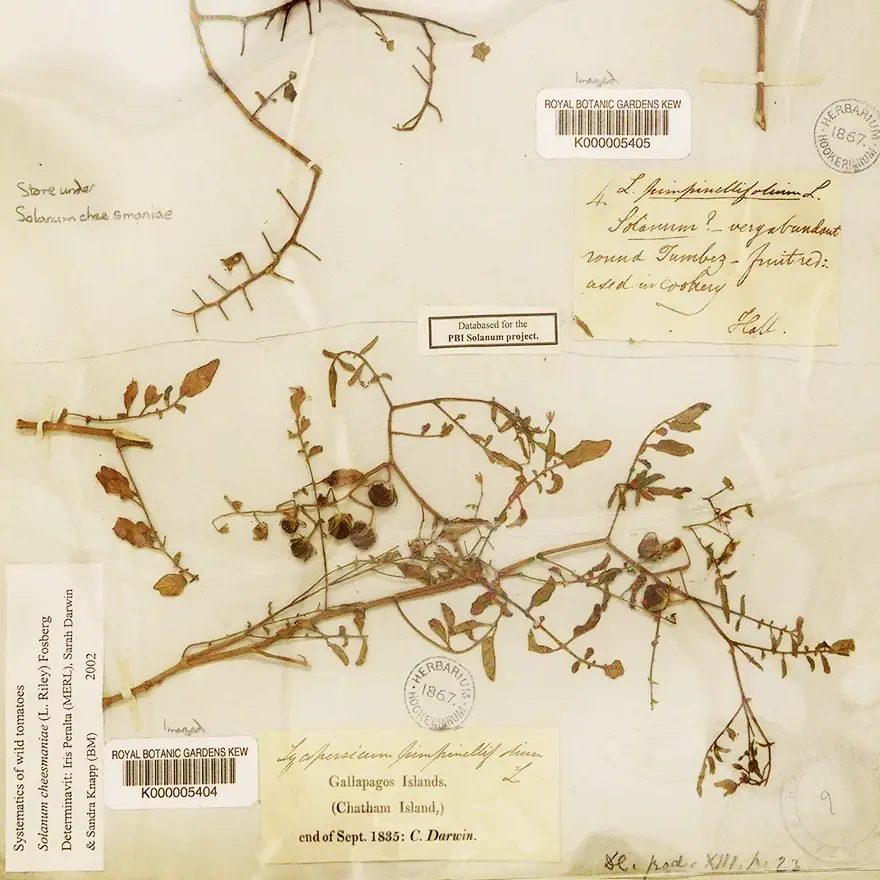

Between the 1700s and the 1900s, botanists used the vasculum to transport plants collected on their travels. They created their own herbarium plant collections for further study.

Building an herbarium plant collection requires a systematic, step-by-step approach: Collecting plants, identification, pressing (using plant-presses and vasculum), drying, mounting on labeled plates, preservation, and storage.

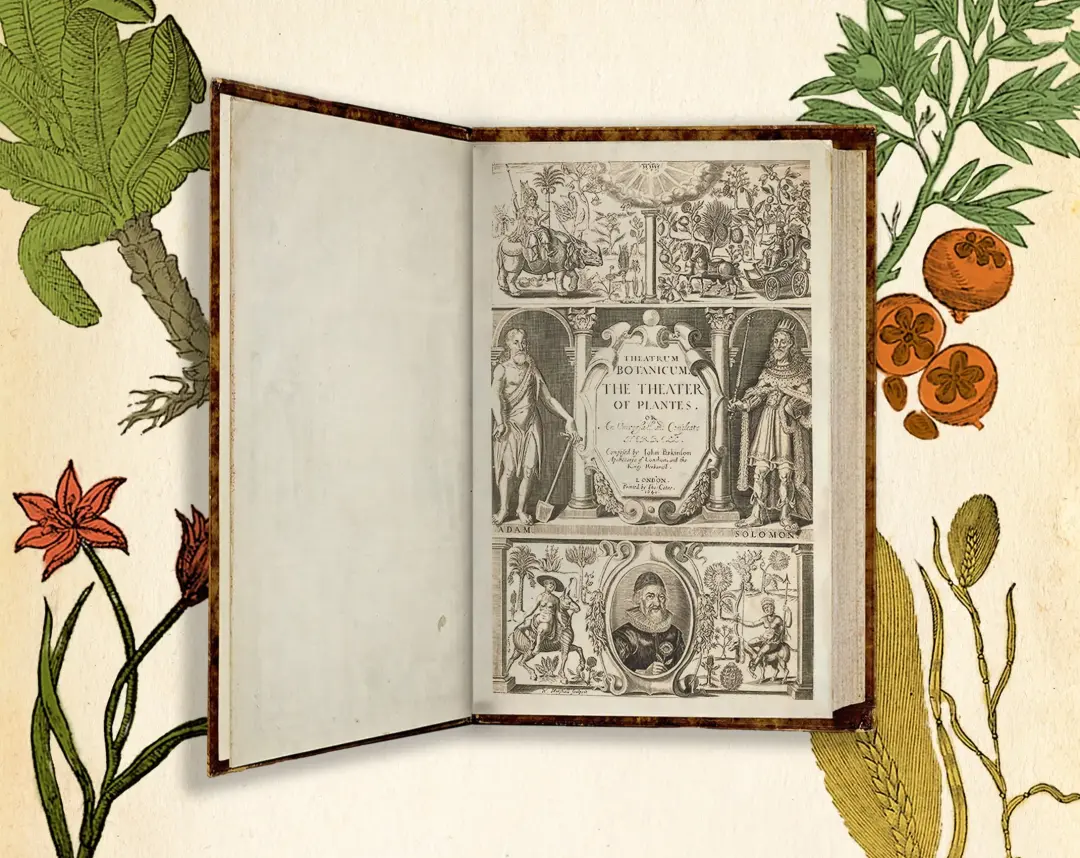

Botanical gardens and their research facilities around the world maintain more than 3,000 pressed plant collections, many of which are centuries old.

The oldest herbarium in existence was created by the Italian naturalist Gherado Cibo in the 16th century.

The largest collections are at: Natural History Museum in Paris; The Royal Botanica Gardens at Kew: 7 million+ specimens dating back to 1696; The William and Lynda Steere Herbarium at the New York Botanical Garden: 7.8 million specimens, second largest in the world.

Herbarium collections, along with seed banks and fungus collections, are crucial for the study and conservation of biodiversity.

Joseph Pitton de Tournefort (1656-1708) created one of the first plant collections at the Jardin des plantes in Paris for King Louis XIII.

The University of Neuchâtel in Switzerland has over 475,000 plant specimens that are now being digitized for science and study. Philosophers and writers, such as Jean-Jacques Rousseau, emphasized the importance of learning about nature. He lived in the Age of Enlightenment, when scientific evidence was gaining importance.

It is important to know where museum collections are from and how the objects came to be there. Especially for botanical gardens like Kew Gardens, that have colonial histories. They now use technology, research, and outreach programs to increase access and understanding of their collections.

Botanical gardens around the world

80% of all biodiversity

Indigenous peoples hold important knowledge about local plants and their usage. Historically, botanists and others relied on their knowledge when exploring new territories. Today, 80% of the world’s biodiversity is protected by indigenous communities. A quarter of the world's land is owned, managed, used, and occupied by indigenous peoples.

Collecting or preserving?

Native American tribes living in North America learned about plants and animals from their elders. They often passed down ideas and knowledge for generations. Much of this knowledge was gained without collecting or endangering nature to study it. Today, many plants are protected from collection because they are endangered.

What is progress?

Indigenous peoples often have a unique way of understanding and relating to nature and the natural world. Historically, this has been seen as the opposite of progress – thought to be things like railroads, factories, and technology. Today, many people look to indigenous knowledge and ways of life to help reduce pollution and care for nature.

Want to know more

Bibliography

BOTANICAL HISTORY

Hodacs, H. (2018). Linnaeus, natural history and the circulation of knowledge. Oxford: Voltaire Foundation.

Le Guyader, H., & Norwood, J. (2018). L’aventure de la biodiversité : de Ulysse à Darwin, 3000 ans d’expéditions naturalistes. Paris: Belin.

PLANT HUNTERS

Barrow, Mark V. (2000). “The Specimen Dealer: Entrepreneurial Natural History in America’s Gilded Age,” Journal of the History of Biology 33 (2000).

Carine, M. (2020). The collectors: creating Hans Sloane’s extraordinary herbarium. Natural History Museum.

Lemmon, K. (1968). The golden age of plant hunters. [éditeur non identifié].

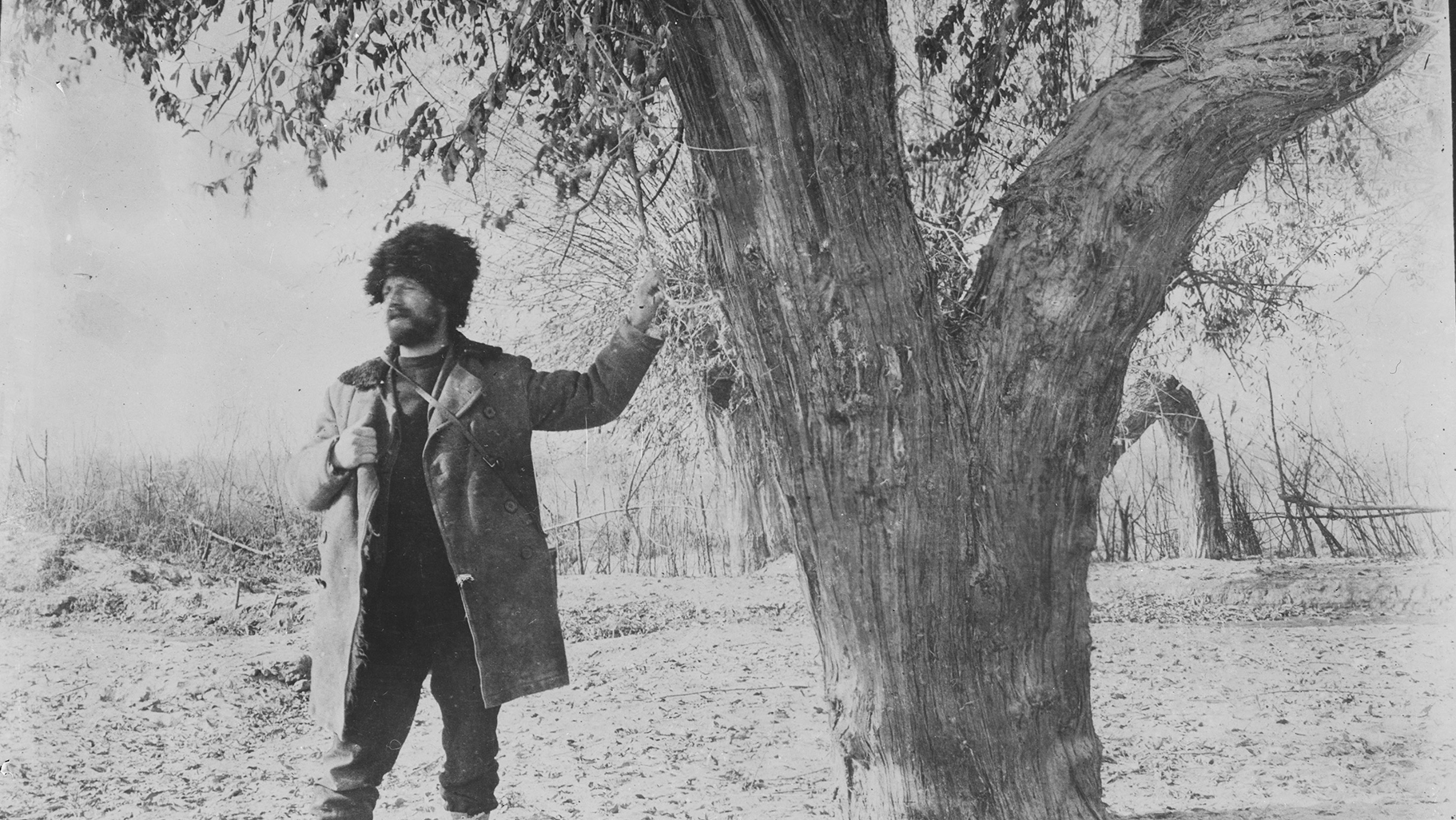

Chacko, Xan Sarah (2018): When life gives you lemons: Frank Meyer, authority, and credit in early twentieth-century plant hunting. History of Science 2018, Vol. 56(4) 432 –469 DOI: 10.1177/0073275318784124 journals.sagepub.com/home/hos

Cunningham, Isabel Shipley, Frank N. Meyer (1984): Plant Hunter in Asia. Ames: Iowa State University Press.

De Vries, Hugo, The Mutation Theory: Experiments and Observations on the Origin of Species in the Vegetable Kingdom, Vol. 2 (Chicago: Open Court Publishing Company, 1909)

Edwards, A. (2021). The plant-hunter’s atlas: a world tour of botanical adventures, chance discoveries and strange specimens. Greenfinch, an imprint of Quercus Editions Ltd.

Endersby, J. (2008), Imperial Nature: Joseph Hooker and the Practices of Victorian Science (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2008)

Fry, C. (2009). The plant hunters: The adventures of the world’s greatest botanical explorers. Andre Deutsch.

Garland E. Allen (1969) “Hugo de Vries and the Reception of the Mutation Theory,” Journal of the History of Biology 2 (1969): 55–87

Harris, A. (2015). Fruits of Eden: David Fairchild and America’s plant hunters. University Press of Florida.

Kingsbury, Noël, Hybrid (2009): The History and Science of Plant Breeding (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 2009)

WOMEN BOTANISTS AND PLANT COLLECTORS

Bilston, S. (2008). Queens of the garden. Victorian women gardeners and the rise of gardening advice text. . Victorian Literature and Culture, 36(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1060150308080017

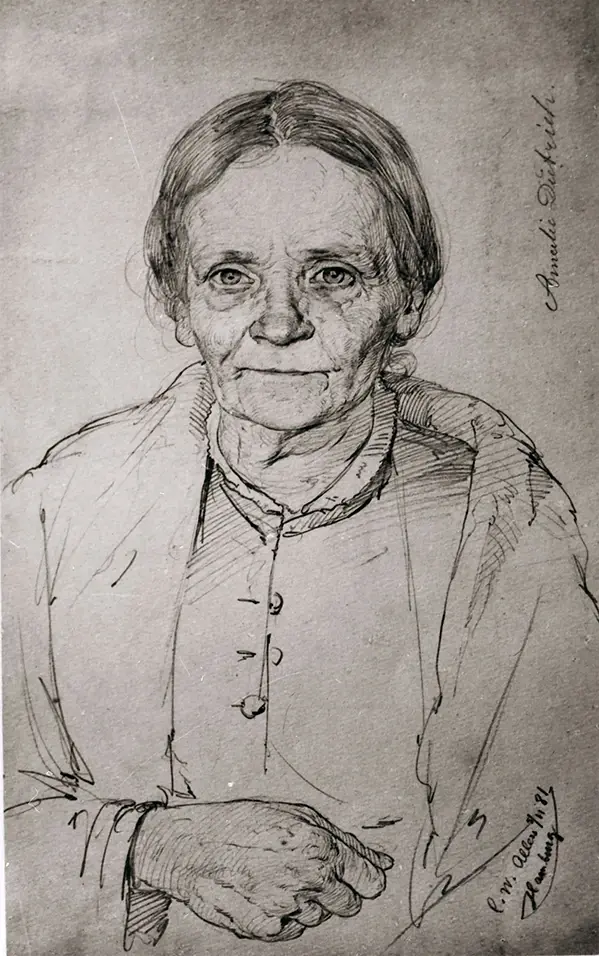

The Dietrich Project – Virtual exhibition about the work and findings of the German, self-taught botanist and plant hunter Amelie Dietrich. Figueiredo, E., & Smith, G. F. (2021). Women in the first three centuries of formal botany in southern Africa. Blumea, 66(3), 275–307. https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2021.66.03.10

Logan, G. B. (2004). Women and botany in risorgimento Italy . Nuncius, 19(2), 601–628. https://doi.org/10.1163/182539104X00377

Madsen-Brooks, L. (2009). Challenging science as usual. Women’s Participation in American Natural History Museum Work, 1870-1950. Journal of Women’s History, 21(2), 11–38. https://doi.org/10.1353/jowh.0.0076

Olsen, P. (2013). Collecting ladies : Ferdinand von Mueller and women botanical artists. Canberra, ACT: NLA Pub.

Rindlisbacher, J., & Cohen, A. (2020). Growing Wild: The Correspondence of a Pioneering Woman Naturalist from the Cape. Oxford: Basler Afrika Bibliographien. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1b0fx9w

Shteir, A. B. (1996). Cultivating women, cultivating science : [Flora’s daughters and botany in England 1760 to 1860]. Baltimore [et autres: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tepe, E. J., Ridley, G., & Bohs, L. (2012). A new species of Solanum named for Jeanne Baret, an overlooked contributor to the history of botany. PhytoKeys, 8(8), 37–47. https://doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.8.2101

THE WARDIAN CASE

Keogh, L. (2017). The Wardian Case: How a Simple Box Moved the Plant Kingdom. Arnoldia, 74(4).

Liu, H.-Y. (2012). From cabinets of curiosities to exhibitions: victorian curiosity, curiousness, and curious things in charlotte brontë. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Shirai, Y. (2003). Ferndean: Charlotte Brontë in the Age of Pteridomania. Brontë Studies : Journal of the Brontë Society, 28(2), 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1179/bst.2003.28.2.123

COLONIAL BOTANY

Allain, Y.-M. (2013). Une Histoire des Jardins Botaniques: Entre Science et Art Paysager. Versailles: Quae.

Ayers, E. (2019). Strange Beauty: Botanical Collecting, Preservation, and Display in the Nineteenth Century Tropics. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Endersby, J. (2016). Deceived by orchids: sex, science, fiction and Darwin. The British Journal for the History of Science, 49(2), 205–229. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007087416000352

Grove, Richard(1995), Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995)

Hong, J. (2021). Angel in the House, Angel in the Scientific Empire: Women and Colonial Botany During the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Notes and Records: The Royal Society Journal of the History of Science, 75(3), 415-438. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsnr.2020.0046

Kingsland, Sharon E.(2005), The Evolution of American Ecology, 1890–2000 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005)

Klemm, D. (2020). Foraged flora : exploring the culinary potential of wild edible plants. University of Georgia Press.

Kloppenburg, Jack Ralph (1988), First the Seed: The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology, 1492–2000 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988)

Rice, R. (2020). “My dear Hooker”: the botanical landscape in colonial New Zealand. Museum History Journal, 13(1), 20–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/19369816.2020.1766296

Royal Botanic Gardens, K. (n.d.). Indian and Colonial Botanic Gardens - The Pamphlet Collection of Sir Robert Stout: Volume 6. Victoria University of Wellington Library, Wellington.

Swan, Claudia (eds.), Colonial Botany: Science, Commerce, and Politics in the Early Modern World (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 200

PLANT HUNTERS

Bush, E. (2012). The Plant Hunters: True Stories of Their Daring Adventures to the Far Corners of the Earth (review). Bulletin of the Center for Children’s Books, 65(9), 480–480. https://doi.org/10.1353/bcc.2012.0407

Butler, S. A. (2016). A Plant Hunter’s Legacy: Japanese Trees in a New England Landscape, 1870–1930. Winterthur Portfolio, 50(2/3), 99–149. https://doi.org/10.1086/688739

Chacko, X. S. (2018). When life gives you lemons: Frank Meyer, authority, and credit in early twentieth-century plant hunting. History of Science, 56(4), 432–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0073275318784124

Edwards, A. (2021). The plant Hunter’s atlas : a world tour of botanical adventures, chance discoveries and strange specimens. London: Greenfinch.

Musgrave, T., Gardner, C., & Musgrave, W. (2000). The plant hunters: two hundred years of adventure and discovery around the world. London: Seven Dials. Primrose, S. B. (2019). Modern Plant Hunters: Adventures in Pursuit of Extraordinary Plants. London: Pimpernel Press.

Short, P. (2003). In pursuit of plants : experiences of nineteenth & [and] early twentieth century plant collectors. Portland: Timber Press.

PLANT AND SEED INDUSTRY

Mabey, R. (2015). The cabaret of plants: botany and imagination. Profile Books Ltd.

Saunders, G. (1995). Picturing plants: an analytical history of botanical illustrations. University of California Press.

Secord, Anne (1994), “Science in the Pub: Artisan Botanists in Early Nineteenth-century Lancashire,” History of Science 32 (1994): 269–315

INDIGENEOUS KNOWLEDGE ABOUT PLANTS AND THEIR PRESERVATION

Clarke, P. A. (2008). Aboriginal Plant Collectors. Botanists and Australian Aboriginal People in the Nineteenth Century. Rosenberg Publishing. ISBN: 9781877058684.

Shiva, V. (1992). Women's Indigenous Knowledge and Biodiversity Conservation. India International Centre Quarterly, 19(1/2), 205-214.

EMILY DICKINSON, GARDENING AND POETRY Bianchi, M. D. (1990). Emily Dickinson’s Garden. Emily Dickinson International Society Bulletin, 2(2), 1-2, 4. Farr, J. (2004). The Gardens of Emily Dickinson. Harvard University Press. McDowell, M. (2019). Emily Dickinson’s Gardening Life. Timber Press. Emily Dickinson’s Herbarium. (n.d.). Harvard’s Houghton Library. Retrieved from http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/4184689?n=1&res=3&imagesize=1200